Surprising Discovery: Researchers Reveal True Diet of the Megalodon

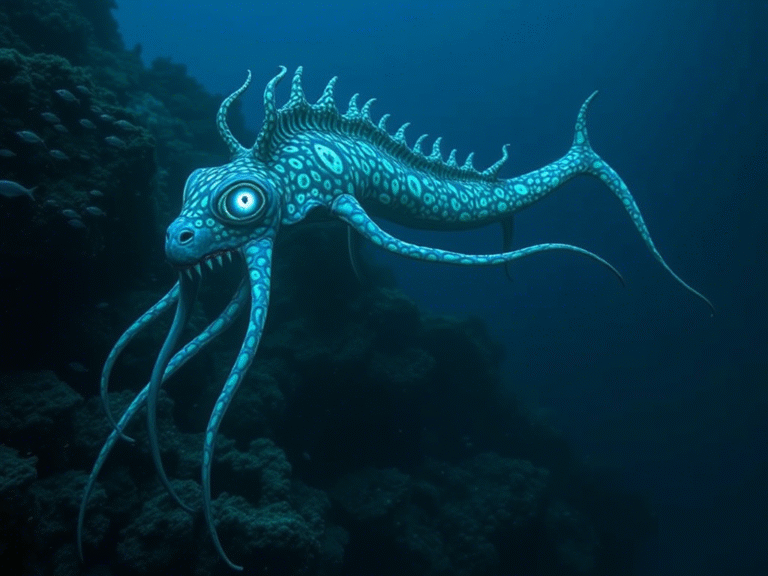

For around 20 million years, the giant prehistoric shark Megalodon ruled the oceans as the ultimate predator — until it vanished during the Neogene period.

During its reign, this massive shark was an opportunistic hunter, feeding on nearly anything it encountered. It didn’t specialize in one type of prey; if it was big enough to be a meal, Megalodon took advantage.

This conclusion comes from a recent study comparing the teeth of modern sharks with fossilized megalodon teeth — the primary evidence we have of this extinct giant.

The findings challenge earlier assumptions that whales were its main food source. While Megalodon certainly hunted whales, its diet was much broader and adaptable.

“Based on our research, Megalodon appears to have been a highly versatile predator,” says geoscientist Jeremy McCormack from Goethe University Frankfurt in Germany. “It could switch between marine mammals and large fish, feeding at various levels of the food chain depending on what was available.”

Megalodon was a massive prehistoric shark that roamed the oceans from about 23 million to 3.6 million years ago, ruling as an apex predator before going extinct. Because shark skeletons are made mostly of cartilage, which doesn’t fossilize well, we have very few remains — mostly teeth and a handful of vertebrae. As a result, its exact appearance remains a mystery.

Still, scientists estimate Megalodon could reach lengths of up to 20 meters (65 feet), with some outlier estimates suggesting even larger sizes. At that size, researchers believe it likely hunted large prey.

One way to uncover what such ancient creatures ate is by studying the chemical signatures in their teeth. Isotopes — variations of elements with different numbers of neutrons — can reveal dietary habits, among other things. By analyzing these isotopes, scientists can piece together what Megalodon really fed on.

When we eat, tiny amounts of metals from our food replace some of the calcium in our teeth and bones. These traces are too small to notice, but they’re enough for scientists to analyze. McCormack and his team focused on the levels of two zinc isotopes — zinc-64 (lighter) and zinc-66 (heavier — in shark teeth.

In the food chain, animals at lower levels — like small fish — retain more zinc-66 compared to zinc-64. But as you move up the chain, predators accumulate less zinc-66. At the very top, apex predators show the lowest ratios of zinc-66 to zinc-64 — exactly what the researchers found in Megalodon and its ancestor, Otodus chubutensis .

Because the exact base of the food web 18 million years ago is unclear, the team compared Megalodon teeth with those of modern sharks to better understand its diet.

“Species like sea bream, which feed on shellfish and crustaceans, represented the bottom layer,” McCormack explains.

“Next came smaller predators like requiem sharks and early cetaceans — ancestors of whales and dolphins. Further up were larger sharks such as sand tigers, and at the very top were giant sharks like Araloselachus cuspidatus and the Otodus lineage, including Megalodon .

Megalodon has long been recognized as a top predator, sitting at the pinnacle of the marine food chain. New research now shows that the zinc isotope differences between Megalodon and lower-level marine animals weren’t drastic — a sign that the giant shark wasn’t picky about its meals.

Interestingly, diet varied depending on location. For example, Megalodon individuals whose teeth were found in Passau, Germany, appeared to consume more prey from lower in the food web.

This flexible, opportunistic feeding behavior is similar to that seen in modern great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias ). In fact, earlier research by McCormack suggests that the rise of the great white may have played a role in Megalodon ’s extinction, as competition for food and habitat increased pressure on the giant shark.

“Studying Megalodon gives us a window into how ocean ecosystems have evolved over millions of years,” says paleobiologist Kenshu Shimada from DePaul University. “More importantly, it reminds us that even the most dominant predators aren’t immune to extinction.”

This research was recently featured in Earth and Planetary Science Letters