How a Common Bacterium Can Damage Your Heart

A new study from Hiroshima University reveals that Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis), a bacterium commonly linked to gum disease, can escape the mouth, travel through the bloodstream, and settle in the heart’s left atrium — where it causes fibrosis , or scarring, that disrupts normal heart rhythm and increases the risk of atrial fibrillation (AFib) .

AFib is a serious condition that raises the chances of stroke, heart failure, and other life-threatening complications. Over the past decade, cases have nearly doubled worldwide — rising from 33.5 million in 2010 to nearly 60 million by 2019 — prompting scientists to look for possible triggers beyond traditional risk factors.

For years, doctors have noticed a connection between periodontitis (a severe form of gum disease) and heart problems . Research has shown that people with gum disease are about 30% more likely to develop AFib. But until now, the reason behind this link wasn’t clear.

Earlier studies pointed to inflammation as one possible factor: when gums become infected, immune cells release chemicals into the blood that can cause widespread inflammation. But researchers have also found DNA from oral bacteria inside the heart muscle, valves, and even artery plaques — suggesting that bacteria themselves may be directly involved.

This new research, published in Circulation , offers the first solid evidence that P. gingivalis can reach the heart — and not just in animals, but in humans too.

“While we still don’t know if periodontitis directly causes AFib, our findings suggest that oral bacteria like P. gingivalis could be part of the pathway,” said Dr. Shunsuke Miyauchi, the study’s lead author and assistant professor at Hiroshima University.

“This bacterium is already known to play a role in diseases far beyond the mouth — including Alzheimer’s, diabetes, and some cancers. Now we have strong evidence that it may also contribute to heart rhythm disorders.”

So next time you’re tempted to skip brushing or flossing, remember: your oral health might affect more than just your smile.

How Gum Bacteria Might Trigger Heart Rhythm Problems

To understand how Porphyromonas gingivalis — a major cause of gum disease — could affect heart health, researchers at Hiroshima University conducted a controlled study using mice.

They used the aggressive W83 strain of the bacterium and introduced it into the tooth pulp of one group of healthy male mice. A second group was left uninfected. The mice were then divided further and observed for either 12 or 18 weeks to track the long-term effects on heart function.

Using a technique called intracardiac stimulation — which helps doctors assess the risk of irregular heartbeats — the team found no significant difference in atrial fibrillation (AFib) risk between the two groups after 12 weeks.

However, after 18 weeks, the results changed dramatically:

Mice infected with P. gingivalis were six times more likely to develop abnormal heart rhythms. About 30% of them showed signs of AFib, compared to just 5% in the control group.

These findings support the idea that long-term exposure to this oral pathogen may play a role in the development of heart rhythm disorders like AFib.

From Mouth to Heart: Confirming the Bacterial Invasion

To make sure their mouse model accurately reflected real periodontitis, researchers examined the animals’ jaws and found clear signs of infection: tooth pulp decay , microabscesses , and other damage caused by P. gingivalis .

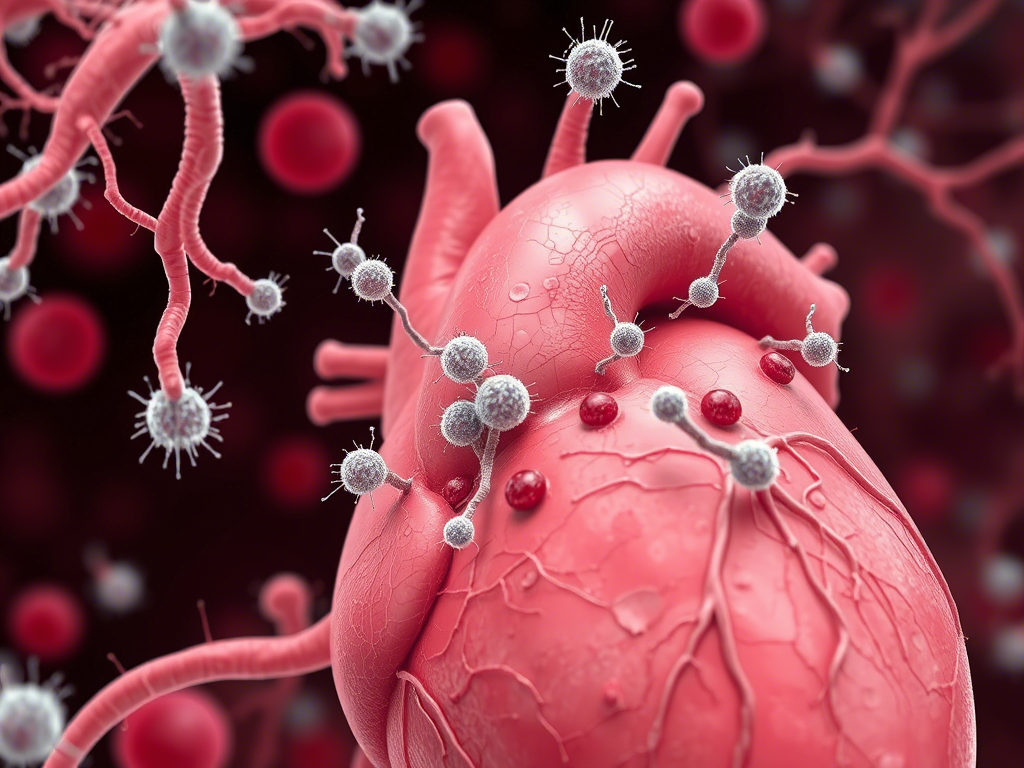

But the effects weren’t limited to the mouth. The team also discovered the bacterium inside the left atrium of the heart , where infected tissue had become stiff and scarred — a condition known as fibrosis .

Using a sensitive genetic technique called loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) , they confirmed that the exact strain of P. gingivalis they had introduced was present in the heart tissue. No traces were found in the control group, whose teeth and hearts remained healthy.

Even more concerning:

After 12 weeks, infected mice already showed more heart scarring than uninfected ones. By week 18, fibrosis levels in the infected group reached 21.9% , compared to just 16.3% in the control group — suggesting that P. gingivalis doesn’t just cause heart damage, it may accelerate it over time.

And the pattern wasn’t unique to mice. In a parallel study of 68 AFib patients , the same bacterium was found in heart tissue removed during surgery — with higher levels in those who also had severe gum disease.

These findings offer strong evidence linking oral health to heart rhythm disorders and highlight the importance of treating gum infections early.

How a Sneaky Bacterium Sabotages the Heart

Porphyromonas gingivalis , the bacterium behind many cases of gum disease, is more than just a mouth problem — it’s a master of stealth. Past studies have shown that this germ can invade human cells and hide from the body’s cleanup system , known as autophagosomes. By doing so, it slips past the immune system, causing just enough inflammation to do damage without getting destroyed.

In infected mice, researchers found elevated levels of galectin-3 , a known marker for fibrosis, and increased activity of the Tgfb1 gene , which plays a key role in inflammation and scarring. These findings support the idea that P. gingivalis doesn’t just reach the heart — it actively makes things worse once there.

The good news?

Simple oral hygiene habits like brushing, flossing, and regular dental checkups may do more than keep your smile healthy — they could also help protect your heart by preventing this bacterium from entering the bloodstream.

As Dr. Shunsuke Miyauchi, the study’s lead author, explained:

“P. gingivalis enters the bloodstream through gum infections and eventually reaches the left atrium of the heart. There, it worsens fibrosis and increases the risk of atrial fibrillation (AFib). By treating gum disease early, we might be able to block this pathway.”

To take their research further, the team is now studying exactly how P. gingivalis affects heart muscle cells. They’re also working on building a collaborative medical-dental care system in Hiroshima Prefecture — with plans to expand it nationwide — to improve prevention and treatment of AFib and other cardiovascular conditions linked to oral health.